The universe may be 2 billion years younger, study finds

How old is the universe? Science does not yet have the definitive answer to this question, and once again a group of researchers comes up with a number that questions the previous consensus.

Scientists measure the age of the universe by considering the speed with which stars move using the Hubble constant , one of the most relevant cosmological values. It turns out that the Hubble constant is not a given value and varies by some estimates. Even so, some researchers prefer to refer to it as a Hubble parameter.

The most accepted age is from a universe of 13.9 billion years old, based on a Hubble constant of 70, which was calculated by reference to WMAP satellite data collected in 2006.

The figure presented by the authors in the most recent study, published by the journal Science, is 84, which would lead to a calculation of 11.4 billion years, ie, the universe would be 2 billion years younger.

How did the universe rejuvenate?

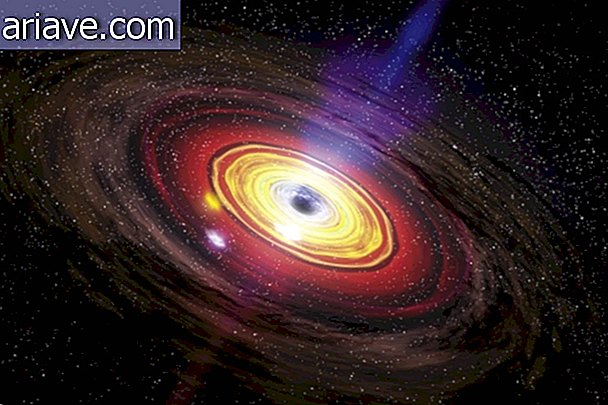

Inh Jee, Max Plank Institute Researcher In Germany, she is the lead author of the study, which used a new way to define this controversial issue. She and her team performed a careful analysis using gravitational lenses formed when light from distant bright objects such as quasars bends around a massive object such as a galaxy located between the receiver and the emitter.

This approach is one of the few that has led to a rather divergent Hubble constant number in recent years, reopening an astronomical debate that has not had much heated discussion for some time. In 2013, a team of European scientists examined the radiation from the Big Bang and declared the slowest expansion rate: 67. In March 2019, Nobel Prize-winning astrophysicist Adam Riess of the Space Telescope Science Institute used NASA super telescope and had a value of 74.

Jee and her team's calculation, however, has a very high margin of error, so it is possible that this "rejuvenation" of the universe may not actually be sustained.

Harvard astronomer Avi Loed, who had no involvement with the study, said it was an interesting and unique way of calculating the rate of expansion of the universe, but because of this large margin of error it will be necessary to gather more information to corroborate its effectiveness. "It's hard to be sure of your conclusions if you use a ruler you don't completely understand, " he says.

Lucky we don't have to have a birthday party for the universe, or we would have trouble buying the right candle to put on the cake.