Starlite: The Mysterious Fireproof Plastic

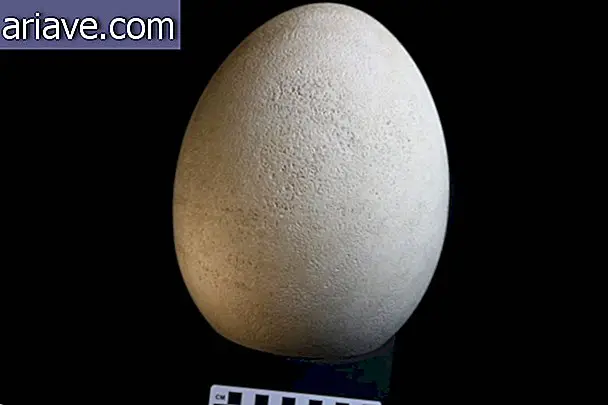

It is virtually impossible to watch the video above without being intrigued by what the images show. The presenter points the flame of a blowtorch directly at the shell of an egg and it is as if nothing happens: it remains intact, not bursting, let alone cracking. At some point you can see that it turns red, but the presenter finds that it is only slightly warm.

That is definitely not an ordinary egg. It was coated with a thin layer of Starlite, a material invented by Maurice Ward in the early 1990s, which served as a strong thermal insulator. At the time, this innovation seemed to be the solution for many areas, as it could be used to cover airplanes, electronics, doors and any object that needs high temperature protection.

However, Maurice Ward died in 2011 without ever selling Starlite. One of the latest news about the inventor and his creation hit the media in June 2010, when Ward suggested to the press that the material could be used to block the oil spill caused by BP in the Gulf of Mexico.

But why couldn't such a promising invention be sold? Was it all a fake created by Ward?

The eccentricity of Maurice Ward

More than 20 years later, the world begins to take an interest again in the miraculous material created by Maurice. In an article recently published in New Scientist magazine, a profile is drawn about the personality of the inventor, who did not seem to be a very easy person to deal with.

Ward, who proudly worked as a hairdresser in 1960, also had a small plastics company in northern England. In his spare time, he was an amateur inventor and even bought heavy equipment from a large chemical industry in England. This way Ward could produce his own plastic pieces.

With a white beard, bow tie, and irreverent thoughts, the British inventor has always kept Starlite's formula a secret. When asked by journalists about the method of producing the mysterious material, he often replied that he created it on the kitchen table with a simple food processor, and that among the ingredients were wheat flour and baking powder.

Is Starlite Real?

It seems that Starlite has always been a true invention. There are, for example, tests by laboratories of the British and US governments that prove the existence of the material. In addition, prominent people, such as United Kingdom Ministry of Defense (MDRU) chemist and adviser Ronald Mason, used to compliment Ward's invention.

In 1991, about 18 months after Starlite appeared on the video television program at the beginning of this article, Ward allowed the MDRU to analyze its creation, but on one condition: officials would not try to find out what ingredients were used in the composition. material.

And what is the first thing scientists do when they are investigating unknown material that can withstand absurdly high temperatures? He was right who said "they shoot a very powerful laser at him". MDRU senior scientist Keith Lewis was impressed with the result: The Starlite plate was only slightly damaged after being struck by a laser beam of 1, 000 millijoules per pulse.

Tests were also performed by Atomic Weapons Establishment (AWE), the laboratory responsible for the development and manufacture of atomic weapons in the United Kingdom. At the time, it was proven that Starlite could withstand temperatures above 1, 000 ° C.

Today there is no doubt about the truth of Ward's material, but the inventor's protectionist paranoia prevented Lewis and other researchers from publishing their experiments in scientific journals. However, they found that Starlite was a polymer composed of organic and inorganic materials, including plastic, ceramics and borates.

Ward never talked about Starlite's recipe. One of the few pieces of information he liked to disclose was the fact that the production of this material involved the mixing of 21 components. Even so, Lewis and the UK Ministry of Defense were strongly betting on the success of the invention.

Negotiation difficulties

During the same time, Ward tried to sell his product to potential manufacturers. Several large companies showed interest in Starlite, but Ward was not a very easy person. One day he charged £ 1 million, and the next he raised the price to £ 10 million.

In an interview with New Scientist, Ward's attorney Toby Greenbury says potential partners also struggled to extract technical information from the inventor. Ward simply did not accept the idea that the material should undergo independent scientific research before being marketed. Not even NASA was able to pull information from him.

How does Starlite work?

With Ward's permission, Lewis was able to perform more tests in another lab. One of the chemist's surprising discoveries was that Starlite's structure changed with the presence of heat. By observing the material with an electron microscope, he found that the surface of the material could create small holes of 2 to 5 micrometers.

These tiny Starlite holes were like tiny air bubbles in a foam, providing thermal insulation and remaining small enough not to alter the ability to reflect and emit heat. What Lewis found is that Ward had created a "smart" compound that had a fire defense system.

In addition, Starlite emitted no toxic gases when heated, which made it even better for the interior lining of aircraft cabinets. Such research could help Ward gain scientific backing for the production of his compost on an industrial scale. But again, the attempt at negotiation was eventually thwarted by the inventor's insecurity.

Also trying to buy Starlite was aviation giant Boeing. According to the New Scientist story, Ward asked for millions of dollars for the invention, but refused to show the recipe for producing the material. Investors simply would not want to invest in something that could be a scam.

Based on these failed attempts at trade, some say that Ward did not want money, but the merit of having created something so revolutionary. He therefore refused to pass the Starlite to scientists who could represent it commercially.

Does the secret remain with the family?

A few years before his death, Ward gave an interview to a radio station and on the occasion commented that if something horrible happened and he lost his life, the family would know how to proceed with Starlite. For now, the inventor's relatives remain silent.

In a statement to New Scientist magazine, materials engineer and scientist Mark Miodownik says it would be a shame for this compound to be lost or kept secret, as until today it has not been possible to find a polymer capable of withstanding such high temperatures that to keep an egg raw under the flame of a blowtorch.

We can only hope that the Starlite will one day be rigorously tested and perhaps bring a little more security to the world.

Sources: NewScientist, BBC, Maurice Ward, The Verge